Nearly every blockbuster movie of the past 40 years (and possibly before that) has been deliberately structured around something called the “monomyth,” also known as the Hero’s Journey. Star Wars. The Matrix. The Lion King. So were Dan Millman’s book The Way of the Peaceful Warrior, Paulo Coehlo’s The Alchemist and the entire Harry Potter series.

Mythologist Joseph Campbell spent his life analyzing myths across times and cultures, and he discovered that every single myth—going back to Homer’s Odyssey and earlier—followed this structure.

This isn’t a surprise, or at least, it wasn’t to Campbell. The monomyth is the structure of the universal human journey—at least, for those of us who explore beyond the status quo, or what Campbell called the Ordinary World.

If you’ve heard of the Hero’s Journey, you may think of it as being filled with dragons and caves, Darth Vader and Obi-Wan Kenobi, but the point of the Hero’s Journey—the point of every single myth that has ever existed—as Campbell told Bill Moyers in 1988, is transformation of consciousness. It’s an internal journey, externalized by various cultures (including Hollywood) to give resonance to the experience every human undergoes.

Campbell’s landmark book, The Hero With a Thousand Faces, referenced our oneness (the singular Hero is consciousness) as well as our human expressions (the “thousand faces” are the seven billion human expressions of consciousness). But we’re dealing with language, and things can get messy, so “the hero’s journey” also applies to the individual.

Some heroes—the kind that most blockbusters feature—go on swashbuckling adventures (think Indiana Jones). And then, in Campbell’s words:

“The other kind is the spiritual hero, who has learned or found a mode of experiencing the supernormal range of human spiritual life, and then come back and communicated it.”

That “supernormal range of human spiritual life” is consciousness.

Your readers are the original heroes that Campbell was writing about (as are you, as am I, as are we all).

That’s why books and movies that follow this structure are so deeply resonant (or in Hollywood terms, blockbusters). The structure isn’t just for fiction and screenwriters, though. As a nonfiction writer, you can use the Hero’s Journey to create greater resonance with your readers.

Before you can use the structure, though, you need to know what it is. There are actually two parallel Hero’s Journeys, inner and outer.

The Inner Hero’s Journey

Because the hero’s journey is about transformation of consciousness, it’s largely internal.

Writer Christopher Vogler introduced the concept of the Hero’s Journey to Hollywood in 1985, with a memo that changed the industry. His book, The Writer’s Journey, explores the inner and outer journeys step by step, along with examples of how these are brought to life in various movies. I strongly encourage writers of all stripes to read it; the latest version includes sections on the wisdom of the body, labyrinths, polarity/duality as a form of conflict, and catharsis—also known as ‘transformation of the reader.’ I highly recommend that every narrative writer (memoir, story-driven nonfiction, and fiction) read Vogler’s book.

He also identified what a character (or person) experiences internally at each stage of the Hero’s Journey.

The Hero’s Inner Journey, from Christopher Vogler [Notes in italics are my comments]

1. Limited awareness of problem — The Ordinary World [status quo]

2. Increased awareness of need for change

3. Fear, resistance to change

4. Overcoming fear

5. Committing to change (crossing the threshold)

6. Experimenting with new conditions

7. Preparing for major change

8. BIG change, with a feeling of life or death — [Dark Night of the Soul, aka Ordeal]

9. Accepting consequences of new life (acceptance of ‘what is’ — my interpretation)

10. New change and rededication (hesitation to re-engage with the 3D world)

11. Final attempts [to hold onto ego] and last-minute danger (of returning to unconsciousness)

12. Mastery

No wonder so many seekers look to “enlightenment” as some final destination. And yet, as Campbell explained to Bill Moyers in the landmark interview series The Power of Myth, and as many of us know, the grail—nirvana, awakeness, Reality, whatever you call it—is a state inside us; it’s not some distant location or an experiential destination. Learning to access it in each moment—mastery—is the Hero’s Journey. It’s an extremely subtle, internal process.

“Eternity isn’t some later time; eternity isn’t a long time; eternity has nothing to do with time. Eternity is that dimension of here and now which thinking in time cuts out.” —Joseph Campbell, in conversation with Bill Moyers (1988)

The Outer Hero’s Journey

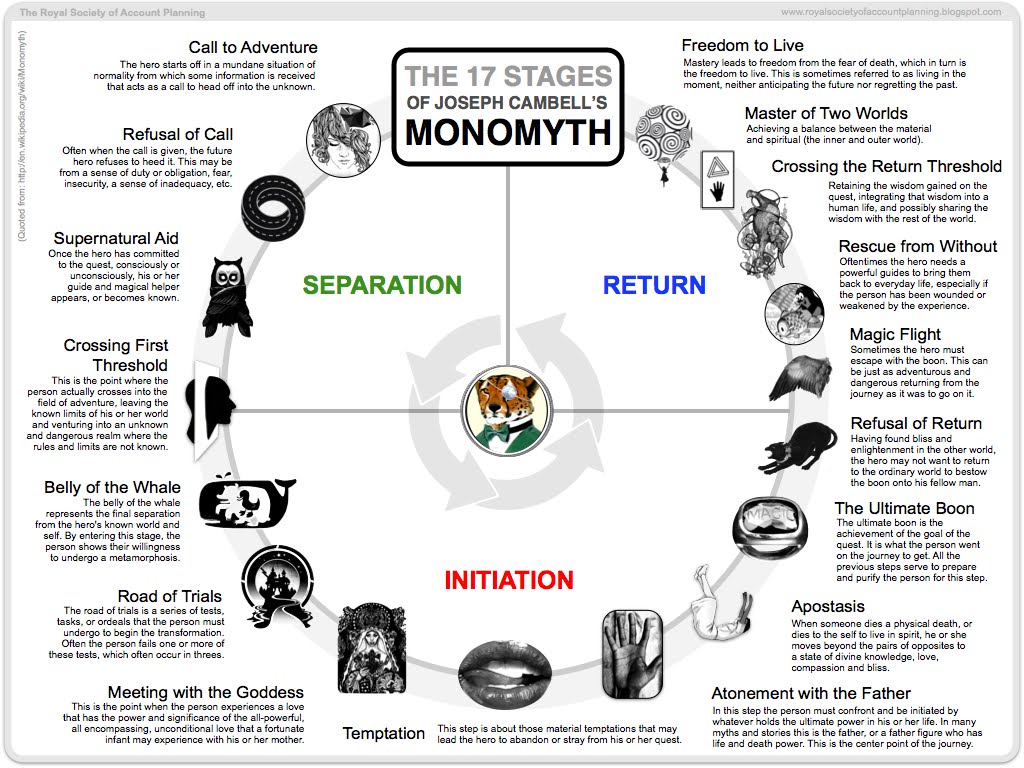

As Carl Jung once wrote, “Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.” So aspects of the Hero’s Journey will show up externally, as well as internally. This is what the Outer Journey looks like (sorry, you may have to zoom in to read the descriptions):

The path is populated with archetypes, including the Mentor, Shadows, Heralds and Threshold Guardians. The latter, for example, might show up as a passive-aggressive boss, a patronizing physician, or fear of success (crossing the threshold away from agreements one has made, consciously or subconsciously, to stay in a certain ‘comfort zone’). Our Ordeals (written here as Initiation) can be anything from divorce to death of a loved one to financial loss. A whole slew of people went through Ordeals when they lost their homes and savings during the Recession—and anecdotally, many began realizing that they were not their homes or possessions or perceived status.

According to Campbell, in his conversation with Moyers, the dragon (in European mythology) is the ego. It guards gold and virgins, but think about it: A dragon can’t use gold, and it has no use for human virgins. (Symbolically, virgins represent pure consciousness here.) “Conquering” the dragon means untethering yourself from ego identification. Drinking the dragon’s blood (which is a part of many myths) symbolizes absorption of its power.

By ‘saving’ ourselves (salvation=awakening), Campbell says we ‘save,’ or help to awaken, the world. By bringing our vitality to the world—by deviating from the force of conformity and power-over structures—we vitalize it.

Many people talk about Star Wars as a metaphor for Buddhism, and screenwriters (as I’ve mentioned) use the Hero’s Journey structure religiously (pardon the pun). But to Campbell, the Dark Side is unquestioning identification with mind. (It’s also any system that people blindly adhere to, without considering what the creative force of the soul wants. “Bliss,” as in Campbell’s often-misinterpreted phrase “follow your bliss” is the creative force of the soul. It’s not “do what feels pleasurable” but “follow your soul’s desire.”)

External journeys are, broadly speaking, more film-able. Or at least, more bankable at today’s box office. So Hollywood tends to shun the subtlety of internal conflict for explosions, car chases and ‘winning’ pleasurable experiences rather than consciousness.

Think about your favourite novels or movies, then look at this chart with the protagonist in mind. Can you make the connection between events in the book or movie and these stages? (If not, a quick Google search will help you.)

How to Use the Hero’s Journey in Narrative Nonfiction

Journey matters, even in nonfiction. The Hero’s Journey is all about transformation. That makes it even more important when writing directly about transformation.

You don’t have to fictionalize your story in order to use the Hero’s Journey structure. If you’re writing narrative nonfiction, that is, nonfiction that tells a story), consider mapping your topic along this path, finding key events from each stage (based on the facts of your life or research), and bringing them forward as the scaffolding of your story. They exist for all of us. It’s not a matter of inventing Threshold Guardians and Mentors. It’s a matter of looking at our lives, or even our data, and identifying those transformational moments. (This is also why it’s so important to show your own Ordeal—people want to know that you’ve been through your own challenges and come out the other side.)

The Hero’s Journey in Straight or Practical Nonfiction

It’s a little more difficult to incorporate the stages of the Hero’s Journey into practical nonfiction. But it’s not impossible. One of the keys to resonance is to know which stage of the journey your reader is in. (See the next post, The Seeker’s Journey) You can also use examples or case studies—from your own life, others’ lives (with their permission), composite/fictional examples, or metaphors—that illustrate the relevant stages. Businesses and organizations, too, go through their own Hero’s Journeys. I believe the United States is now in its biggest Dark Night of the Soul since the Civil War.

With straight nonfiction, your reader is the Hero, and your subject may also be a Hero—yet it’s even possible to use this structure, to some extent, when organizing a book on, say, how to cook.

When a reader picks up a book, generally they expect something to happen—either within the book, or within themselves. Your task as a writer, is to know your reader, illuminate the moment she finds herself in, to identify it and offer a roadmap (or compass, depending on your style) to help her navigate the terrain. By identifying where you want the reader to be after finishing your book, you can determine how much content is enough.

The Hero’s Journey both is and isn’t a one-shot deal. On the spiritual level, it’s an overarching cycle; few of us ever attain Mastery. On a smaller scale, it’s a continual spiral. We finish one journey and embark on another throughout our lives.

In the coming weeks, I’ll look at the Seeker’s Journey (a phrase I think I’ve coined) and differing views on women, the Hero’s Journey and the Heroine’s Journey.

As you look at the structures of the Hero’s Journey, how can you see your own life reflected?

This post contains affiliate links. If you purchase an item after clicking the link, I may earn a small commission.